It appeared by late 1992 that a new world order had been ushered in along with an end to the balance of terror. No longer would Western nations and the Soviet Union snarl at each other while threatening Mutually Assured Destruction.

The Russian empire had collapsed and now Western-style democracy, freedoms and civil rights would spread globally – communism was dead, long live capitalism and self-determination!

Francis Fukuyama suggested in his book ‘The End of History and the Last Man’ that the collapse of the Soviet Union was in fact not only ‘the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such’ in which, he promised ‘Western liberal democracy as the final form of government’ would reign supreme.

For the ordinary Russians it truly was the worst of times, with a drunken President Boris Yeltsin at the helm, once subservient territories (like Ukraine) breaking away, the economy in the toilet, anarchy on the streets. The once mighty USSR had been trashed and utterly humiliated, a wasted knight expiring inside his tarnished, rusty armour.

Flying to St. Petersburg, in order to report on a defence diplomacy visit by the Royal Navy survey ship HMS Herald, I was somehow lodged with my UK Ministry of Defence minder in run down hotel that displayed the sign: ‘Closed forever.’ It seemed rather suitable as a description for the fate of the entire Soviet Union.

Later, after taking a ride on a Russian Navy hydrofoil across the freezing Gulf of Finland to Kotlin Island and Kronstadt naval base, I visited a warship moored in a basin. During a social event held aboard, I drank 16 vodka toasts with a Russian admiral and his aides, much to the consternation of officials in the British delegation I was accompanying. Each toast was accompanied by zakuski – ‘little eats’ – to soak it up and more than once the Russian admiral suggested we should salute ‘the beautiful women of the world!’

A junior officer of the Baltic Fleet had a private chat with me, pondering the sad fate of the once mighty Russian Navy, which, he said, was flogging its submarines to Iranians while its sailors sold the uniforms off their backs to feed their families. He sighed that he was now more an office worker than a mariner.

During the same trip, I went to visit the politician in city hall with responsibility for running one of the St. Petersburg naval shipyards. He wondered what to do about the thousands of workers employed in building a new nuclear-powered battlecruiser. This was a ship that would be named after Tsar Peter the Great, the fearsome ruler who founded the city and the Navy in the early 1700s. Yet now Russia’s Navy seemed to be redundant and so, naturally, it was feared the shipyard workers were too…but how would their families cope?

However, in visiting St Petersburg three years later, on the occasion of the frigate HMS Chatham’s turn as UK flagship for VE Day 50 anniversary events, I found the battlecruiser was somehow still being built, albeit not very swiftly.

To get a look at the vessel, I took a taxi across town, which cost 20 US dollars one way, which, I reflected, was quite extraordinary, especially as the previous day I had visited a hospital in the city and met a paediatrician who made a mere $30 a month.

The taxi driver agreed to wait while I walked to a spot where, sure enough, I could see the towering structure of the Peter the Great looming over the shipyard. I took a few stealthy snaps, which didn’t turn out very well.

Three years later that warship was commissioned and ended up as the flagship of the Arctic-based Northern Fleet. In 2014 and 2016 the 28,000 tons RFS Peter the Great (or Pyotr Velikiy to use the correct Russian name) was off British shores, escorting the former Soviet Navy’s sole carrier, RFS Admiral Kuznetsov. In 2016 both the battlecruiser and carrier headed for the eastern Mediterranean to shore up the Assad regime in the Syrian civil war.

It was all part of President Vladimir Putin’s bid to resurrect Russian naval power and safeguard his nation’s southern flank. During both deployments, Peter the Great was shadowed when close to the UK by the British Type 45 destroyer HMS Dragon.

Today RFS Peter the Great is at sea again, heavily armed with a variety of missiles and leading a combat exercise that is being run simultaneous to numerous other deployments of the Russian Navy, some of which may switch to becoming war missions against Ukraine.

RFS Peter the Great – and the two dozen or so other Russian warships also on exercise in the Barents Sea right now – are a means to keep NATO busy on its northern flank while President Vladimir Putin makes up his mind about whether or not his ground forces should storm into Ukraine.

Back in the early 1990s, nobody would have imagined the Russians would ever complete a warship as massive as Peter the Great, or commission the behemoth, never mind retain that vessel in service 30 years after the St. Petersburg shipbuilding boss fretted it was a dead project.

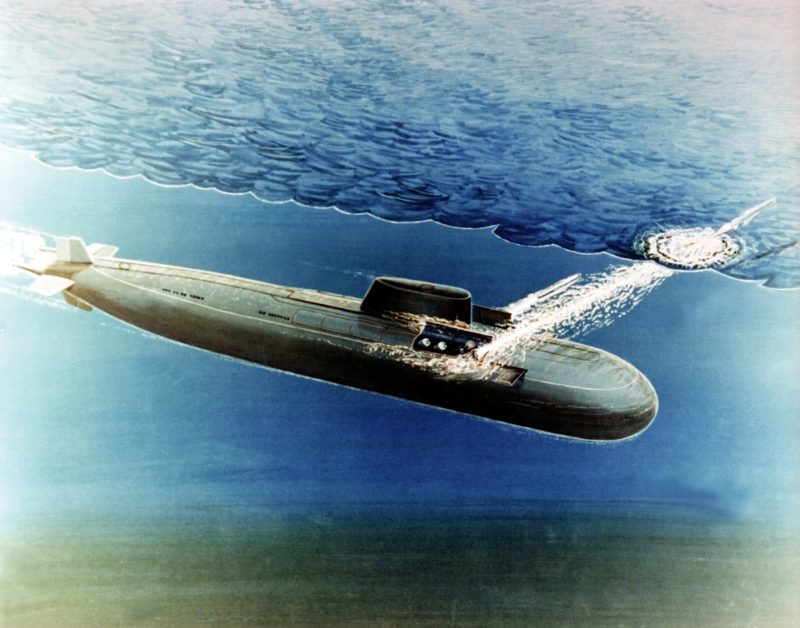

These days the West needs to keep an eye not so much on RFS Peter the Great, as new generation submarines such as the Belgorod, a 30,000 tons (dived) nuclear-powered multi-role vessel. A variant of the Oscar II guided-missile boat (SSGN), Belgorod is designed to launch nuclear-tipped, nuclear-propelled Poseidon inter-continental torpedoes, each with a two-megaton warhead. Belgorod will become operational this year.

The Belgorod even acts as mother ship for a 90ft-long submarine that can be deployed on special missions. In 1992 the very idea of that kind of vessel would have seemed a pipedream for the supposedly bankrupt Russians. Today such craft are the very stuff of nightmares for the West, as Putin makes clear his determination to field a whole new generation of wonder weapons at sea while menacing a near neighbour with massive armed force on land.

-

This is a revised and updated version of an article that appeared in the June 2019 edition of WARSHIPS IFR.

-

For more on the Ukraine Crisis, including Russian Navy activities, see the March edition of WARSHIPS IFR and watch out for further posts on this web site. The magazine will be available in both hard copy and digital versions.

-

The naval side of the Ukraine Crisis is discussed in the latest episode of our WARSHIPS POD podcast.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item